NYC's Property Tax System Creates Unaffordable Housing

The city's real property tax structure disincentivizes dense urban housing while advantaging single-family housing by a ratio greater than 4:1.

This post draws from research into the New York City Department of Finance (DOF) real property tax levy and how this is applied to housing. A side-by-side comparison calculating the effective tax rate of two $4mn properties can be found here.

(Do Ho Suh, Apartment A, Unit 2, Corridor and Staircase, 348 West 22nd Street, New York, NY 10011, USA (detail), 2011–2014)1

This deep dive reveals how multifamily property owners pay up to five times the effective tax rate of single-family homeowners in New York City—a hidden cost passed directly to renters undermining the city's ability to create market-rate housing that New Yorkers can afford. Simplifying and balancing effective tax rates on residential property would do more for housing affordability in NYC than our current policies.

Welcome to Range NYC. If this is your first time here, consider starting with A Note on Content, which outlines the intentions for this publication. You can also read through the About page to learn more.

Range NYC publishes occasional thought pieces about real estate development and construction management in NYC. The posts are long-format and dive into specific issues often covered in series. Topics may relate to policy, technical details of project execution, or deal analyses. Any insights are derived from lived experience.

Key Points

NYC's housing crisis isn't just about supply—it's artificially exacerbated by a tax system that charges 4.6x higher rates to multifamily buildings.

Single-family homeowners enjoy a privileged 6% tax assessment ratio on their market value, while dense, urban apartments face a punishing 45% tax assessment ratio on their market value.

Balancing effective tax rates between property classes would do more for true affordability than the current patchwork of complex incentive programs.

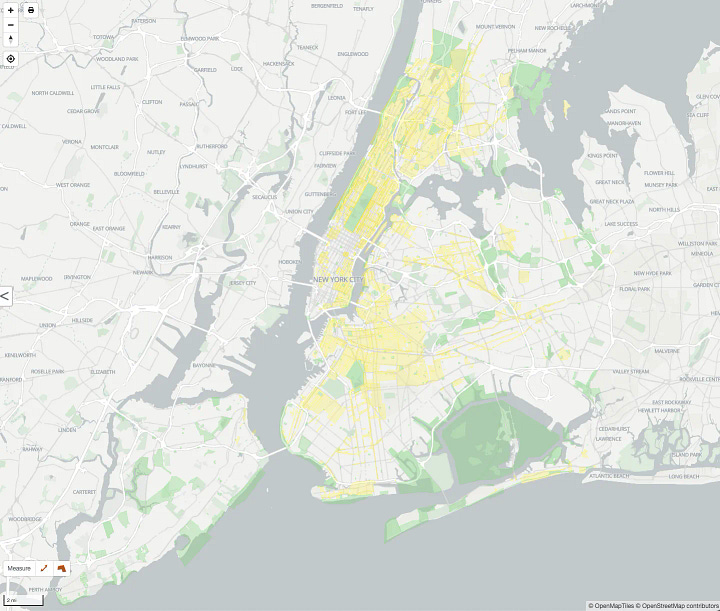

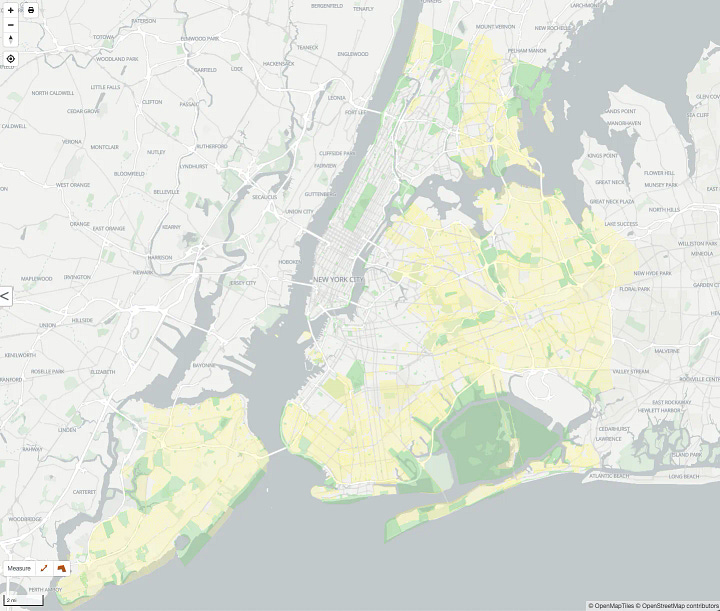

(Google Earth image showing that by land area, NYC is predominantly a low-rise city of single-family homes)

The Inaccurate Assessment of Housing Affordability

NYC's housing affordability crisis has reached a breaking point. The city faces an existential challenge with a vacancy rate of just 1.4%—the lowest since 1968—and median market-rate one-bedroom apartments exceeding $4,500 monthly. For context, affordability should mean spending no more than 30% of income on housing as defined by HUD, but with a median household income at $79,713, the affordable threshold for the average New Yorker is closer to $2,000 monthly—less than half what the market demands.2

The math simply doesn't work. While policymakers implement programs like 485-x (replacing the expired 421-a abatement), City of Yes zoning reforms, and office conversion incentives, they consistently miss addressing the fundamental structural problem: NYC's property tax system actively penalizes multifamily housing.

This penalty isn't a slight discrepancy. It's a structural distortion that channels wealth from renters in large-dense multifamily properties to property owners of single-family homes in New York City. Multifamily buildings shoulder an effective tax rate nearly five times higher than comparable single-family homes.

The consequences extend beyond individual hardship. Since the pandemic, NYC has lost over 540,000 residents, with housing costs undoubtedly driving much of this exodus. Left unchecked, this population decline threatens the city's economic foundation and cultural vibrancy. Instead of right-sizing the underlying issues and letting markets do their work, we continue to add layers of complexity to an already constrained housing market that has become predominantly rent-regulated, with wildly unaffordable market rate units offsetting these constraints.

How the Tax System Disincentivizes Density and Affordability

The city's property tax system operates through four classes, with residential properties split between Class 1 (single-family homes and buildings up to three units) and Class 2 (multifamily buildings with more than three units). The headline tax rates—19.963% for Class 1 and 12.235% for Class 2 as of 2022—create the illusion that multifamily housing receives preferential treatment. The reality is precisely the opposite.

The Department of Finance calculates property taxes through a nine-step process (a link to a side-by-side comparison can be found here), with three critical components creating massive disparities:

Valuation Methodology: Class 1 properties are valued based on comparable sales, while Class 2 properties use an income capitalization approach that often inflates their assessed values.

Assessment Ratios: This is where the system truly tips in favor of single-family properties. Class 1 properties are assessed at just 6% of their market value, while Class 2 properties face a staggering 45% assessment ratio—a 7.5x difference before tax rates even apply.

Growth Caps: Class 1 assessed values can increase by no more than 6% annually and no more than 20% over five years, insulating single-family homeowners from market fluctuations while Class 2 properties rise with the market.

The real-world impact is stunning. Two properties worth $4 million in market value would generate wildly different tax bills: approximately $42,000 for the Class 1 property versus $193,000 for the Class 2 property—a 4.6x difference that inevitably flows through to renters in the form of higher market-rate rents that have become unaffordable for the vast majority of New Yorkers. Add to this the staggering $106bn city budget annually. How real property taxes are used to balance city finances, and the situation is only likely to worsen in the coming years.3

(Left Image: R6 through R10 zoning/tax Class 2 primarily. Right image: R1 through R5 zoning/tax Class 1 primarily.)

This isn't merely a technical distinction; it represents a systematic transfer of cost burden from homeowners to renters (typically lower and middle-income New Yorkers), contributing to affordability challenges and making "housing that people can afford" mathematically difficult to achieve in many parts of the city. This effect is compounded by restrictive zoning artificially caps land supply that could be used to build hundreds of thousands of additional housing units. Recently, other municipalities that have addressed zoning constraints, such as Austin, Texas, have seen this connection play out in real-time. After implementing significant zoning reforms in 2023-2024 that allowed more housing units per lot and reduced minimum lot sizes,4 Austin experienced a notable drop in rental rates as inventory increased. By August 2024, average rent prices in Austin had decreased by approximately 8.5% from their 2022 peak,5 while median rental prices saw their largest annual decline in over 20 years.6

Reconsidering Approaches to True Affordability

Achieving genuine housing affordability requires addressing the underlying structural imbalance rather than continuously adding complex incentive programs to a strained system. It's critical to understand the semantic gap at play: when elected officials discuss "Affordable Housing" (with capital letters), they're referencing a specific regulatory framework—units with rent controls tied to Area Median Income (AMI) percentages or properties developed through various subsidy programs.7 This fundamentally differs from what most citizens reasonably understand as "housing people can afford" (lowercase). The public hears "affordable housing" and envisions attainable market-rate homes within their budget constraints, while officials discuss a narrowly defined category of subsidized units that serve only a small fraction of the population.

The current approach addresses effects rather than underlying causes. While the expired 421-a tax abatement provided valuable incentives for development, its flawed replacement (485-x) offers only temporary relief from an inherently uneven system. Mandatory inclusionary housing creates valuable regulated units, leaving market-rate apartments increasingly out of reach. Each new program adds necessary but complex layers without modifying the fundamental structure.

A more comprehensive solution might include gradually adjusting the balance between the effective tax rates of multifamily and single-family properties. This wouldn't necessitate immediate tax increases for homeowners—a phased approach could achieve greater equity while avoiding disruption to any market segment. Recent NYC Comptroller's Office analysis has modeled scenarios for modifying Class 1 assessment ratios, demonstrating possible approaches.8

The 1920s saw NYC's greatest housing boom, creating neighborhoods like Jackson Heights and the Grand Concourse. During this remarkable period, New York built over 740,000 housing units in a single decade (1920-1929) despite having a population approximately one-third smaller than today.9 This unprecedented construction was largely stimulated by the "Al Smith Law" of 1920, which exempted new housing construction (but not land values) from property taxes until 193110 The policy effectively functioned as a land value tax that incentivized development rather than land speculation. As a result, New York built housing faster than its population grew, creating a buffer of supply that helped the city weather the Great Depression better than other major urban centers.11 Even today, approximately 22% of NYC's current housing stock dates from this decade—more than any other period and all housing built since 1980 combined.12

(Map courtesy of Jason M. Barr of Building the Skyline with date from MapPLUTO)

Rather than continuing to add layers of complexity, we might acknowledge that our current affordability challenges stem partly from structural decisions we've made—decisions that could be reconsidered through thoughtful reform to reignite NYC’s dynamism and start building on the scale we did a century ago.

Rather than adding layers of complexity, we might acknowledge that our current affordability challenges stem partly from structural decisions we've made—decisions that could be reconsidered through thoughtful reform.

Leveling the Playing Field

NYC's property tax system creates a situation where multifamily housing faces nearly five times the effective tax burden compared to single-family homes, contributing to an affordability challenge that existing abatements and incentive programs can only partially address. By considering adjustments to this fundamental imbalance through gradual modifications to assessment ratios and methodologies, the city could encourage the production of market-rate housing at price points more accessible to average New Yorkers, helping to retain population and support the city's continued economic health.

Ever upward.

*This Substack is a work in progress that will endeavor to improve over time. If you are reading this, thank you for making it to the end of the post — you are a part of the community that can improve this content. Please comment, share, and send feedback that can improve future posts. What was left out from the above? How could the argument be taken further? Was the post true to Range NYC’s stated objectives in A Note on Content? Send a message with your thoughts.

From the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA, https://www.lacma.org/): Born in South Korea in 1962, Suh moved to the United States in 1991 and currently lives between London, Seoul, and New York. Inspired by his migration history, Suh’s ethereal, malleable architecture presents an intimate world that is both deeply familiar and profoundly estranged. Do Ho Suh’s works elicit a physical manifestation of memory, exploring ideas of personal history, cultural tradition, and belief systems in the contemporary world. Best known for his full-size fabric reconstructions of his former residences in Seoul, Providence, Berlin, London, and New York, Suh’s creations of physicalized memory address issues of home, displacement, individuality, and collectivity, articulated through the architecture of domestic space.

NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development, “New York City’s Vacancy Rate Reaches Historic Low of 1.4 Percent, Demanding Urgent Action & New Affordable Housing,” February 2024

NYC Department of Finance, "Property Assessment Process," 2024.

The Texas Tribune, "Austin enacts sweeping reforms to cut down housing costs," May 2024.

Team Price Real Estate, "Will Rent Prices Continue to Drop in Austin? Detailed 2024 Analysis," August, 2024.

Team Price Real Estate, "Austin's Median Rental Prices Drop by 2% in 2024: Largest Decline in Over 20 Years," October 2024.

NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development, "Area Median Income," 2023.

Rosenberg & Estis, P.C., "Lowering the Tax Class 1 Assessment Ratios: Exploring the Scenarios Modeled by the NYC Comptroller's Office," August 2024.

BuildingTheSkyLine.org, "The Housing Twenties: New York's Biggest Building Boom and Its Lessons for Today," January 2025.

CHPC New York, "How Tax Incentives Broke the Housing Deadlock in NYC," January 2024.

The Daily Renter, "How a small Georgist reform saved New York City: Al Smith's 1920 property tax reform," January 2025.

Using NYC data for average cost per square foot, apartment sizes, occupancy per apartment and per private homes etc, I calculate that the tax amounts to aproximately $1,000 per month for a typical rental occupant vs $800 per month for a typical luxury home occupant . So it is an extremely regressive tax when you consider the likely income of people owning a $4M home vs someone renting the average NYC apartment. (I use tax per occupant bc the city services funded by the tax are probably best correlated with population size, such as number of kids in a school, or bags of garbage produced per person etc.)